A profound shock to our societies and economies, the COVID-19 pandemic underscores society’s reliance on women both on the front line and at home, while simultaneously exposing structural inequalities across every sphere, from health to the economy, security to social protection. In times of crisis, when resources are strained and institutional capacity is limited, women and girls face disproportionate impacts with far reaching consequences that are only further amplified in contexts of fragility, conflict, and emergencies. Hard-fought gains for women’s rights are also under threat. Responding to the pandemic is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities, but also about building a resilient world in the interest of everyone with women at the centre of recovery. Explore these varied impacts below and take a quiz to test your knowledge. For more information on this topic, visit UN Women's dedicated web page featuring news, resources and more, and learn about our response.

Learn more about UN Women's response to the pandemic »

Page last updated 17 March 2021. Content available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license.

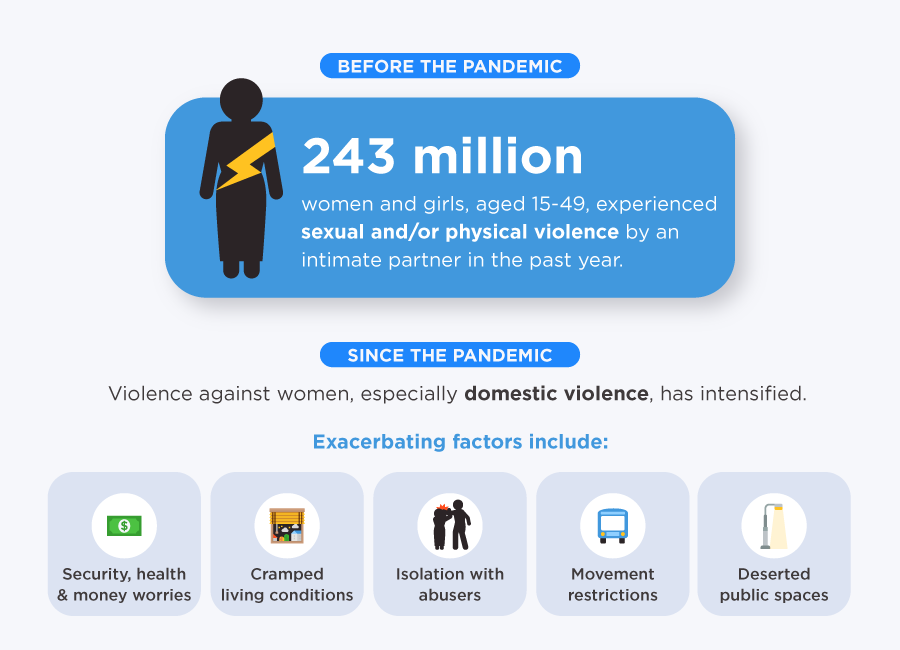

Economic and social stresses combined with movement restrictions and cramped homes are driving a surge in gender-based violence. Prior to the pandemic, it was estimated that one in three women will experience violence during their lifetimes, a human rights violation that also bears an economic cost of USD 1.5 trillion. Many of these women are now trapped at home with their abusers and are at increased risk of other forms of violence as overloaded healthcare systems and disrupted justice services struggle to respond. With more people spending time online with movement restrictions in place, online forms of violence against women and girls in chat rooms, gaming platforms and more are likely to increase. Women –– especially essential and informal workers, such as doctors, nurses and street vendors –– are at heightened risk of violence as they navigate deserted urban or rural public spaces and transportation services under lockdown. The pandemic’s economic impacts are likely to increase sexual exploitation and child marriage, leaving women and girls in fragile economies and refugee contexts particularly vulnerable. In April, UN Secretary-General António Guterres appealed to end all forms of violence everywhere, from war zones to people’s homes, and to focus efforts on ending the pandemic.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, UN, April 2020; COVID-19 briefs on violence against women and girls, UN Women; COVID-19: Emerging gender data and why it matters, UN Women; "Make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of national response plans for COVID-19", UN Secretary-General António Guterres, April 2020. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response; Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic, Statement by Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women

Emerging data shows a deeply concerning trend: COVID-19 is driving a spike in domestic violence and is being compounded by money, health and security stresses, movement restrictions, crowded homes and reduced peer support. In a number of countries, domestic violence reports and emergency calls have surged upwards of 25 per cent since social distancing measures were enacted. Such numbers are also likely to reflect only the worst cases. Prior to the pandemic, less than 40 per cent of the women who experienced violence sought help of any sort. Now, quarantine and movement restrictions further serve to isolate many women trapped with their abusers from friends, families and other support networks. And, the closure of non-essential businesses means that work no longer provides respite for many survivors and heightened economic insecurity makes it more difficult for them to leave. For those who do manage to reach out, overstretched health, social, judicial and police services are struggling to respond as resources are diverted to deal with the pandemic. Building on a call for an immediate global ceasefire, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres in April 2020 appealed to end all forms of violence everywhere, on the battlefield and at home, and urged governments to address the “horrifying global surge in domestic violence” through prevention and redress measures in their national response plans.

To support women and girls facing domestic violence, safe access to support services and emergency measures, including legal assistance and judicial remedies, is urgently needed, but it has been curtailed amid lockdowns in some countries. Measures to protect women from violence must be a standard part of government responses to the pandemic, as well as longer-term recovery packages. This includes ensuring shelters stay open as essential services, or repurposing unused spaces to provide shelter to women and girls who are forced to leave their homes to escape abuse. In addition, shelters need more resources so they can expand to accommodate quarantine needs and increased demand. Also required is greater support to hotlines and women’s rights organizations working on the front lines. Government responses to the surge in violence against women have been uneven. Analysis reveals a range of measures taken, including awareness-raising campaigns, expansion of hotlines and other reporting mechanisms, support for shelters, and measures to address impunity and strengthen women’s access to justice.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, UN, April 2020; COVID-19 briefs on violence against women and girls, UN Women; COVID-19: Emerging gender data and why it matters, UN Women; Transcript of the UN Secretary-General's virtual press encounter on the appeal for global ceasefire, UN, 23 March 2020; "Make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of national response plans for COVID-19", UN Secretary-General António Guterres, April 2020; From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response; Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic, Statement by Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women

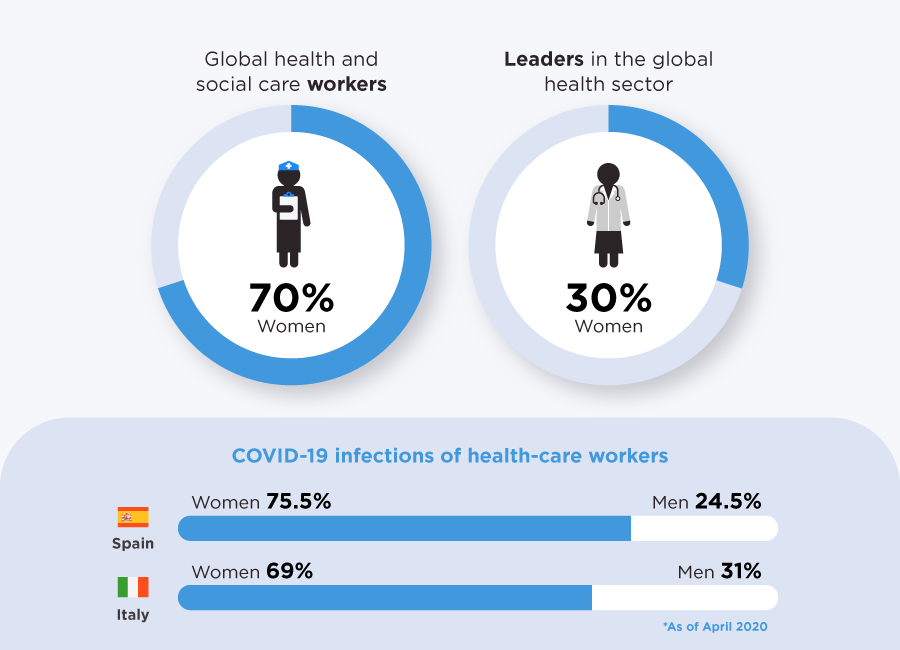

The pandemic is a reminder of the essential contribution that women make at all levels. As health professionals, community volunteers, transport and logistics managers, scientists, doctors, vaccine developers and more, women are at the frontlines of the COVID-19 response. Globally, women make up 70 per cent of the health workforce, especially as nurses, midwives and community health workers, and account for the majority of service staff in health facilities as cleaners, launderers and caterers. Despite these numbers, women are often not reflected in national or global decision-making on the response to COVID-19. Further, women are still paid much less than their male counterparts and hold fewer leadership positions in the health sector. Masks and other protective equipment designed and sized for men leave women at greater risk of exposure. The needs of women frontline workers must be prioritized: This means ensuring that health care workers and caregivers have access to women-friendly personal protective equipment and menstrual hygiene products and are afforded flexible working arrangements to balance the burden of care.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, UN, April 2020; COVID-19: Emerging gender data and why it matters, Gender equity in the health workforce: Analysis of 104 countries, World Health Organization, March 2019; UN Women; Power, privilege and priorities, Global Health 50/50 Report 2020, The UCL Centre for Gender and Global Health. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

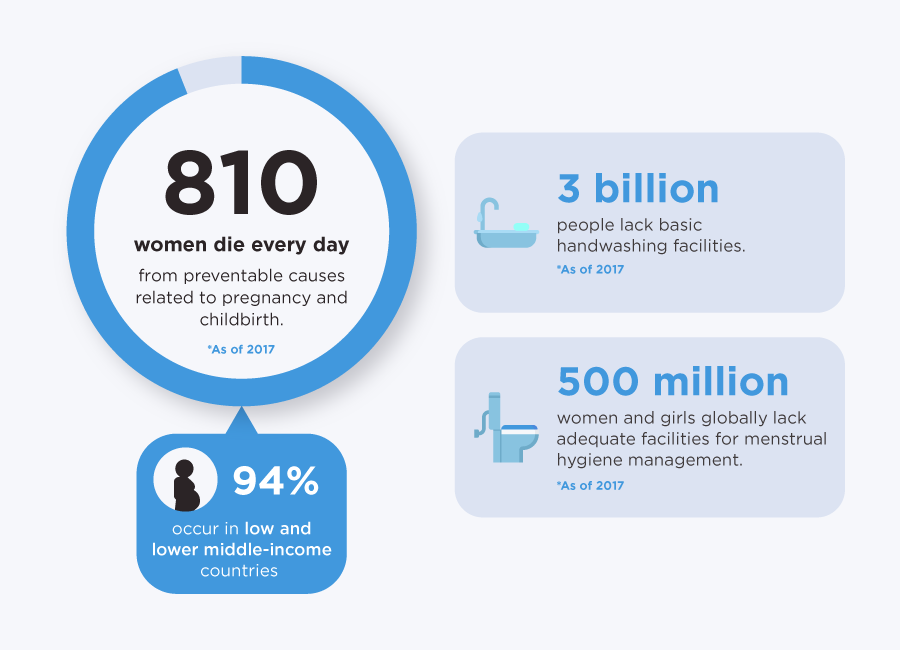

Hand hygiene and sanitation is a critical element in preventing the spread of COVID-19. Yet, 3 billion people, or 40 per cent of the world’s population, do not have a handwashing facility with water and soap at home, according to the latest global estimates from WHO and UNICEF. The world’s extreme poor — 689.4 million, over half of whom are women and girls — living on less than USD 1.90 a day, displaced people and refugees are at immediate high-risk. Women and girls, who already faced health and safety implications in managing their sexual and reproductive health and menstrual hygiene without access to clean water and private toilets before the crisis, are particularly in danger. When healthcare systems are overburdened and resources are reallocated to respond to the pandemic, this can further disrupt health services unique to the well-being of women and girls. This includes pre- and post-natal healthcare, access to quality sexual and reproductive health services, and life-saving care and support for survivors of gender-based violence. The health impacts can be catastrophic, especially in rural, marginalized and low-literacy communities, where women are less likely to have access to quality, culturally-accessible health services, essential medicines or insurance coverage. Before the pandemic, around 810 women died every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth — 94 per cent of these deaths occured in low and lower middle-income countries. One recent study found that if routine health care is disrupted and access to food is decreased, the increase in child and maternal deaths could be devastating: 118 low- and middle-income countries could see an increase of 9.8 to 44.7 per cent in under-5 deaths per month and an 8.3 to 38.6 per cent rise in maternal deaths per month. Past pandemics have also shown increased rates of maternal mortality and morbidity, adolescent pregnancies, and HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Multiple and intersecting inequalities, such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, disability, age, race, geographic location and sexual orientation, among others, can further compound these impacts. Yet, globally, just 37 per cent of COVID-19 cases have been disaggregated by both sex and age as of mid-July 2020.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, Fact sheet: Maternal mortality, World Health Organization, September 2019; Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, Joint Monitoring Programme 2017 update and SDG baselines, World Health Organization, UNICEF; Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Data Website, World Health Organization, UNICEF; Menstrual Hygiene Management Enables Women and Girls to Reach Their Full Potential, The World Bank, May 2018; Poverty data (348.3 million women and girls as well as 341.1 million men and boys lived on less than USD 1.90 per day in 2019), paper forthcoming, UN Women, The World Bank; Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2020, UN Women. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

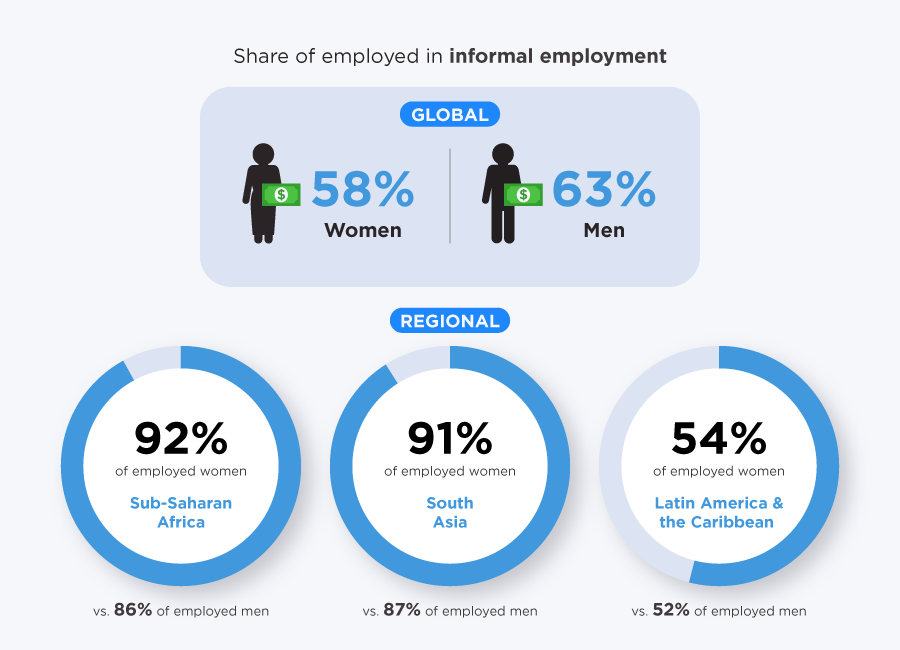

When crises strike, women and girls are harder hit by economic impacts. Around the world, women generally earn less and save less, are the majority of single-parent households and disproportionately hold more insecure jobs in the informal economy or service sector with less access to social protections. This leaves them less able to absorb the economic shocks than men. For many families, school closures and social distancing measures have increased the unpaid care and domestic load of women at home, making them less able to take on or balance paid work. The situation is worse in developing economies, where a larger share of people are employed in the informal economy in which there are far fewer social protections for health insurance, paid sick leave and more. Although globally informal employment is a greater source of employment for men (63 per cent) than for women (58 per cent), in low and lower-middle income countries a higher proportion of women are in informal employment than men. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, around 92 per cent of employed women are in informal employment compared to 86 per cent of men. It is likely that the pandemic could result in a prolonged dip in women’s incomes and labour force participation. During the first month of the pandemic, estimates suggest that informal workers globally lost an average of 60 per cent of their income: 81 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, 70 per cent in Europe and Central Asia, and 22 per cent in Asia and the Pacific.

The ILO estimates global unemployment to rise between 5.3 million (“low” scenario) and 24.7 million (“high” scenario) from a base level of 188 million in 2019 as a result of COVID-19’s impact on global GDP growth. By comparison, global unemployment went up by 22 million during the 2008-9 global financial crisis. Women informal workers, migrants, youth and the world's poorest, among other vulnerable groups, are more susceptible to lay-offs and job cuts. For example, UN Women survey results from Asia and the Pacific are showing that women are losing their livelihoods faster than men and have fewer alternatives to generate income. And, in the U.S., men’s unemployment went up from 3.55 million in February to 11 million in April in 2020 while women’s unemployment – which was lower than men’s before the crisis – went up from 2.7 million to 11.5 million over the same period, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The picture is even bleaker for young women and men aged 16-19, whose unemployment rate jumped from 11.5 per cent in February to 32.2 per cent in April. In 26 of 33 countries with available data, even in male dominated sectors such as manufacturing, women are more likely than men to hold vulnerable/unprotected jobs.

A slowing economy, job losses and lack of social protection are expected to push anywhere from 70 million to 150 million additional people into extreme poverty – a reversal after years of steady decline in poverty rates. New economic forecasts by sex and age using the International Futures Model – commissioned by UN Women and UNDP and prepared by the Pardee Centre at the University of Denver – put the figure at approximately 100 million people, of whom about 50 million are women and girls. The impact, which considers downward revisions in global economic growth, will be even greater if the crisis isn’t controlled enough for normal economic activities to resume. In addition, increased care burdens, a slower recovery or reduced public and private spending on services – such as education or childcare – may push women to leave the labour market permanently.

Unsurprisingly, there are marked regional affects, as well. Today, 55 percent of the world’s poor women reside in sub-Saharan Africa, a share that is expected to grow to 63 percent by 2030. However, and because of the pandemic, Central and Southern Asia, a region that had made significant progress towards poverty eradication, will now comprise 32 percent of the world’s poor women, instead of the previously expected 29 percent. Further, a gender-poverty gap among those aged 25–34 currently exists in 75 of 131 low- and middle-income countries; and only eight of these countries (Bhutan, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Gabon, Guyana, Indonesia, and Nicaragua) are expected to close this gap by 2030. Unless policies are put in place immediately to prevent women’s further impoverishment, an additional 59 countries will need up to 70 years to close their gender poverty gaps.

Despite the clear gendered implications of outbreaks, policy response and recovery efforts have thus far tended to ignore the needs of women and girls. We need to do better. The new data commissioned by UN Women and the United Nations Development Programme estimates the cumulative cost of lifting the world out of extreme poverty by 2030 to be about $2.3 trillion in purchasing power parity terms, or just 0.14 percent of global gross domestic product. The comparative cost of closing the gender poverty gap? Just $49 billion.

Given that the factors driving the current rise in global poverty include the global economic downturn, job losses, and the lack of safety nets, policy solutions may seem obvious. But these must be gender-inclusive and gender-specific if the world is to be brought back on track to eradicate extreme poverty. Our report estimates that by 2030, over 150 million women and girls could be lifted out of poverty by implementing a comprehensive strategy focused on improving access to education, family planning, fair and equal wages, and expanding welfare transfers.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, Fact sheet: Maternal mortality, World Health Organization, September 2019; Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture, International Labour Organization, 2018; COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses, International Labour Organization, 18 March 2020; Surveys show that COVID-19 has gendered effects in Asia and the Pacific, Women Count, UN Women, April 2020; The Employment Situation, April 2020, Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor; Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2020, UN Women; From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women; After the Pandemic, Rebuild for Gender Justice, 2020, Open Society Foundations. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response, UN Women; Spotlight on SDG 8: The impact of marriage and children on labour market participation, UN Women, International Labour Organization, May 2020

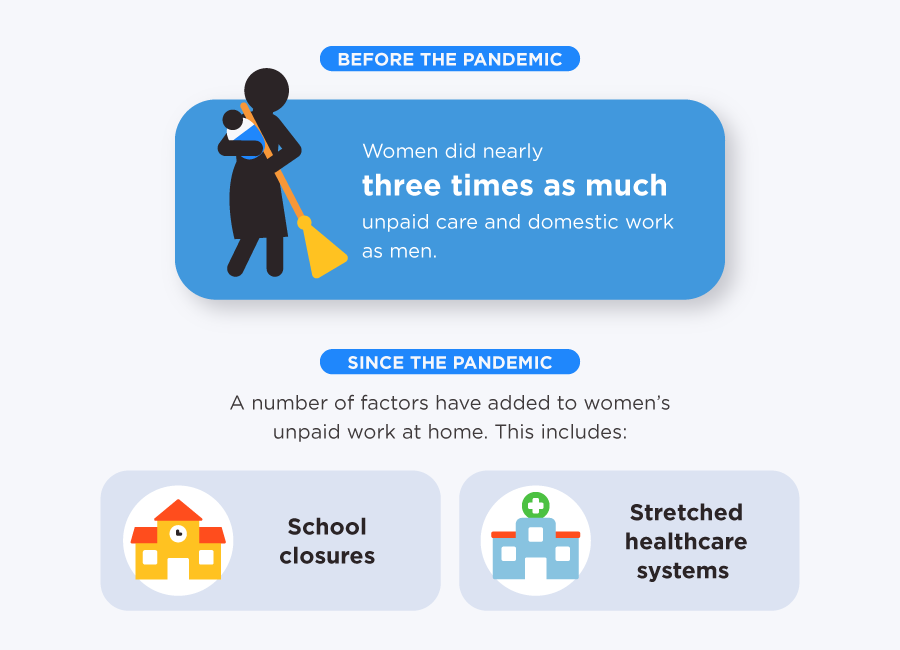

The world’s economies and maintenance of our daily lives are built on the invisible and unpaid labour of women and girls. Before the crisis started, women did nearly three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men. Social distancing measures, school closures and overburdened health systems have put an increased demand on women and girls to cater to the basic survival needs of the family and care for the sick and the elderly. With more than 1.5 billion students at home as of March 2020 due to the pandemic, existing gender norms have put the increased demand for unpaid childcare and domestic work on women. Emerging evidence from UN Women’s rapid gender assessment surveys demonstrates that the disproportionate share of unpaid care work is still falling on women’s shoulders during the pandemic; in fact, they report an increase in unpaid care, often while managing paid work. In slums and slum-like settings with high population density, women are forced to collect water at crowded community pumps, increasing their exposure to the virus. This also holds true in rural contexts, where women are generally responsible for gathering water and firewood. This constrains their ability to carry out paid work, particularly when jobs cannot be carried out remotely. The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers and lone mothers who have care responsibilities. Discriminatory social norms are likely to increase the unpaid work load of COVID-19 on girls and adolescent girls, especially those living in poverty or in rural, isolated locations. Evidence from past epidemics shows that adolescent girls are at particular risk of dropping out and not returning to school even after the crisis is over. Women’s unpaid care work has long been recognized as a driver of inequality with direct links to wage inequality, lower income, and physical and mental health stressors. As countries rebuild economies, the crisis might offer an opportunity to recognize, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work once and for all.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women; Progress of the World’s Women 2019-2020, UN Women; COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response (visit this link for the latest school closure information), UNESCO; Covid-19 school closures around the world will hit girls hardest, UNESCO, 31 March 2020; From insights to action: Gender equality in the wake of COVID-19, UN Women. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response, UN Women; Spotlight on SDG 8: The impact of marriage and children on labour market participation, UN Women, International Labour Organization, May 2020; Unpaid Care Work: Your daily load and why it matters, UN Women, May 2020.

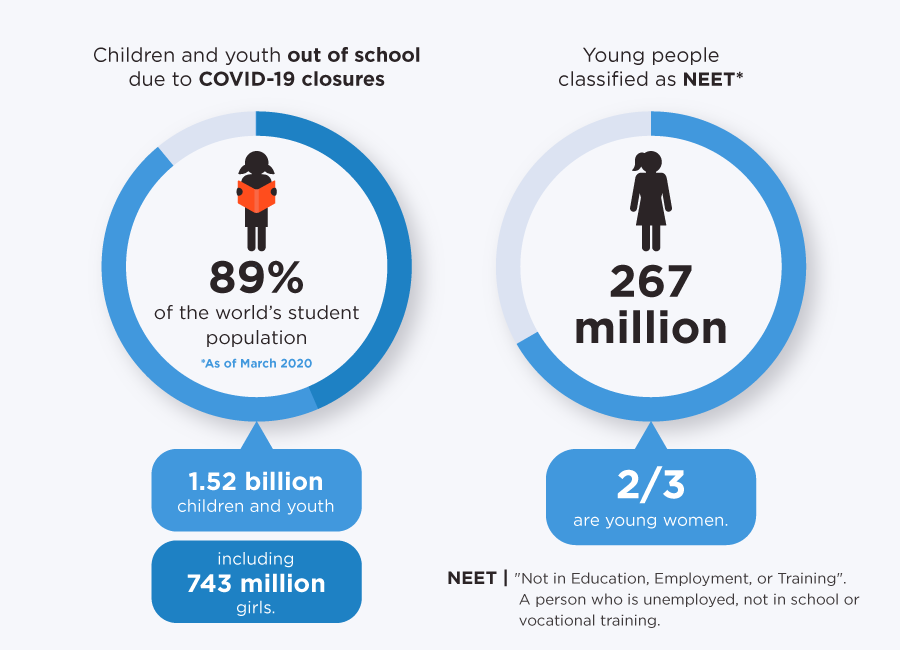

From running awareness campaigns to volunteering support for the elderly to working on the front line, young people are joining efforts at all levels to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, youth, especially young women, indigenous peoples, migrants and refugees, face heightened socio-economic and health impacts and an increased risk of gender-based violence due to movement restrictions, discrimination and more. School closures and overstretched health care systems will also have acute effects on young women and girls. By the end of March 2020, UNESCO estimated that over 89 per cent of the world’s student population were out of school or university because of COVID-19 school closures, forcing many learners online with large parts of the population in low-tech or no-internet environments at a severe disadvantage. Young women and girls living in poverty, with disabilities or in rural, isolated locations are more likely to be pulled out of school first to compensate for increased care and domestic work at home. They are also more prone to child marriage and other forms of violence as families find ways to alleviate economic burdens. Unemployment, too, will hit young people particularly hard: Following the 2008 economic recession, youth unemployment rates were significantly higher in many places than overall averages, and the recent expansion of the gig economy will likely heighten this disparity. Before the pandemic even hit, there was already an upward trend in the number of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET). Out of the some 267 million young people globally classified as NEET, two-thirds, or 181 million, are young women.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women; Progress of the World’s Women 2019-2020, UN Women; COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response (visit this link for the latest school closure information), UNESCO; Covid-19 school closures around the world will hit girls hardest, UNESCO, 31 March 2020; Youth exclusion from jobs and training on the rise, International Labour Organization, March 2020; Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the future of jobs, International Labour Organization, March 2020. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

As COVID-19 spreads, there is an urgent need to stop conflict. Building on a call for an immediate global ceasefire, UN Secretary-General António Guterres in April 2020 appealed to end all forms of violence everywhere, from war zones to people’s homes, to focus efforts on ending the pandemic. Conflict and humanitarian crises hold women and girls back from progress, including the right to food, education, safety and health amid social and economic collapse. Years of war in places like Yemen and Syria have also decimated hospitals and crippled health care systems, leaving people, especially women and children, reliant on humanitarian aid in conflict-affected countries at highest immediate-risk for COVID-19. Before the pandemic, maternal mortality rates were already alarmingly high with 300 deaths per 100,000 live births or more in half of the countries affected by crisis or conflict, according to the latest available data. The further burdening of the health care sector in these contexts will likely increase maternal mortality. Special attention is needed for the unique needs of displaced and refugee women and girls. In refugee camps, for instance, where cramped conditions make physical distancing challenging, women and girls are more prone to gender-based violence when practicing hygiene at latrines or water distribution sites. Women must be part of the solution: Evidence shows that when women are included, peace agreements are more likely to be durable. Yet, they are often excluded from the peace tables and their unique needs and concerns overlooked. In 2019, only 26 per cent of signed peace agreements had gender provisions. In a COVID-afflicted world, we cannot afford to have peace agreements quickly fall apart.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women; Transcript of the UN Secretary-General's virtual press encounter on the appeal for global ceasefire, UN, 23 March 2020; "Make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of national response plans for COVID-19", UN Secretary-General António Guterres, April 2020; E/CN.6/2020/3, United Nations Economic and Social Council, 13 December 2019; PA-X Peace Agreements Database (2020) Version 3. Political Settlements Research Programme, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh; Women’s Participation in Peace Processes, Council on Foreign Relations. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response

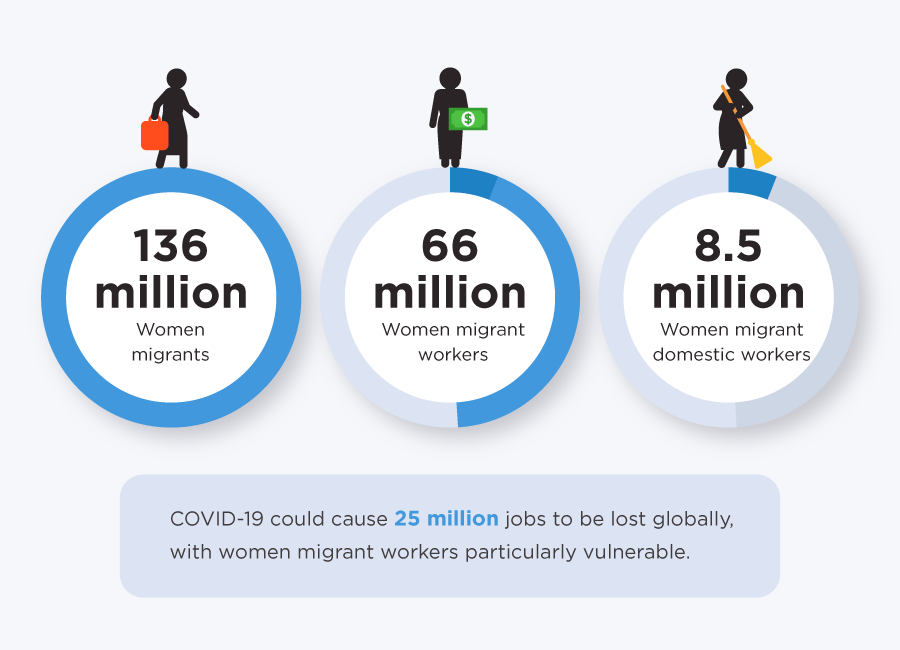

Around the world, migrants are the backbone of health care systems and thriving economies, as doctors, nurses, scientists, researchers, entrepreneurs, essential workers and more, and are at the front line of the COVID-19 response. Already grappling with intersecting forms of discrimination and inequality, women migrant workers face gender-specific restrictions in migration policies, may have limited access to culturally-sensitive essential health services in different languages and are more prone to abuse and sexual and economic exploitation with stricter movement measures, both within nations and across borders. Women migrant workers are also more likely to hold insecure jobs in the informal economy, especially in essential but low-paid jobs as domestic workers, cleaners, laundry workers. Generally excluded from social protections and insurance schemes, this leaves them with limited or no access to health care, lost income benefits and other social and economic safety nets. For many of the 8.5 million women migrant domestic workers, the pandemic has led to loss of income and jobs with their health, safety and well-being often ignored. The economic downturn has left women migrant workers sending fewer remittances, a lifeline for families and communities in their countries of origin, especially during times of crisis.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women, UN, 2020; Guidance note: Addressing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women migrant workers, UN Women, April 2020; COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses, International Labour Organization, March 2020. Related resources: In Focus: Gender equality matters in COVID-19 response