The gendered impacts of migration in Niger

Introduction

Women migrate from, into and through Niger for diverse reasons: from leaving behind poverty, risks of violence and food insecurity to finding work and reuniting with family members. When migration is a choice, it can be an expression of women’s agency and a vehicle for their empowerment which can have positive impacts; it can increase women’s access to employment opportunities, and their autonomy and status. But when migration is a last resort, it can exacerbate women’s and girls’ risks of human rights violations, including to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), trafficking in persons and forced labour. It can also expose women to serious labour rights abuses. In Niger, most migrant women, particularly those that are undocumented, work in the informal economy, mainly in domestic work, without any labour protections.

While there is a significant lack of sex-disaggregated data and gender statistics on migration in the region, this infographic presents some facts and figures on women’s experiences migrating from, into and through Niger.

Explore the impacts

Click on the topic below to learn more.

Women’s migration from, into and through Niger

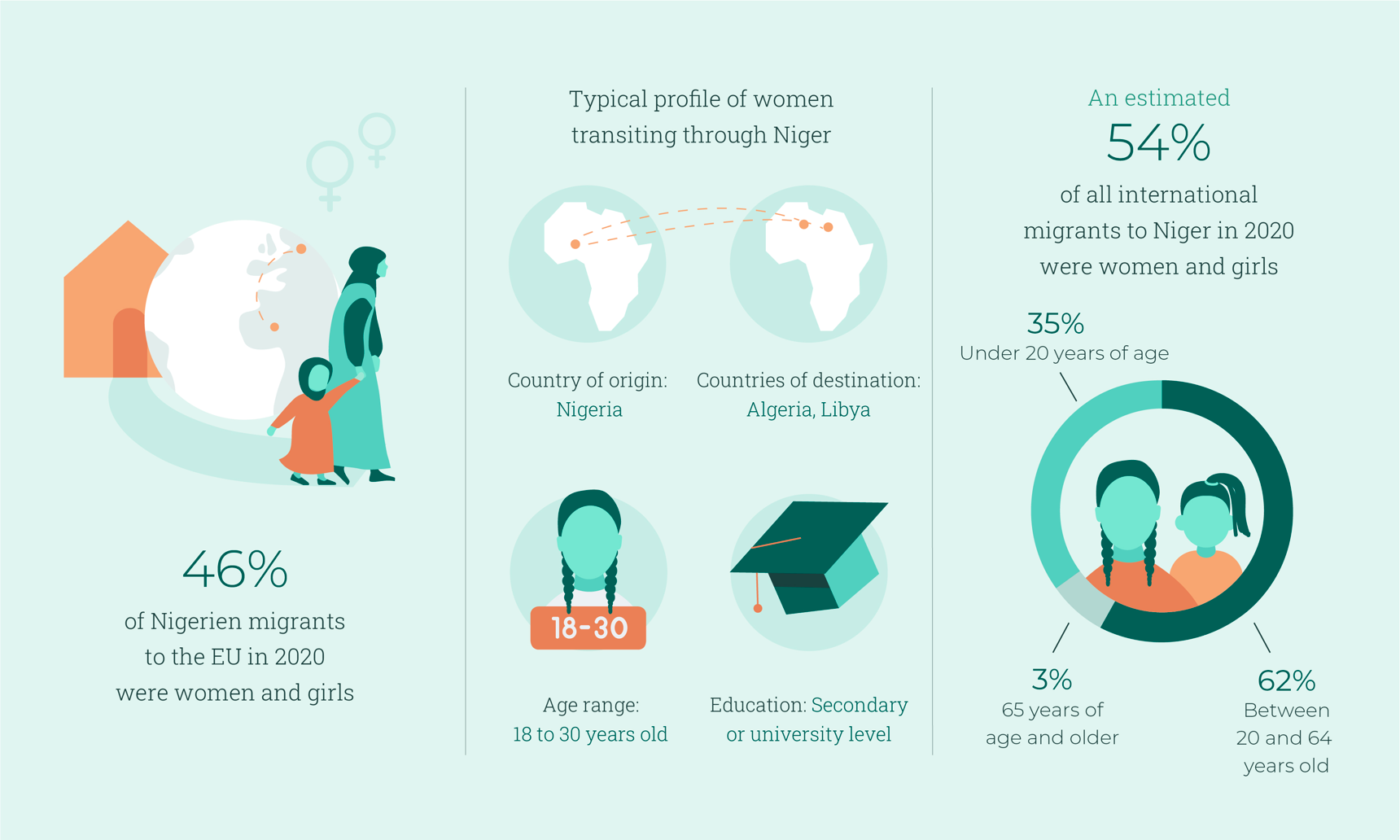

Migrant women from Niger mostly migrate within West Africa and to a lesser extent to North Africa and Europe. In recent years, the number of women migrating from the Zinder and Maradi regions of Niger to Algeria appears to be on the rise, mainly due to a lack of employment opportunities in their communities of origin and cultural factors such as the search for social recognition and respect from their families and communities.

Data from 2020 showed that women and girls comprised approximately 54 per cent of the estimated 350,000 international migrants in Niger, who mainly originate from other countries in Western Africa. Around 65 per cent of women were of working age (20 to 64 years of age). At the crossroads of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and North Africa, Niger has increasingly become a transit country for West African migrant women heading to North Africa and Europe.

Sources: European Commission, DG Migration and Home Affairs. 2015. A Study on Smuggling of Migrants: Characteristics, Responses and Cooperation with Third Countries – Final Report. September; ANLTP/TIM. 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018.” Niamey; Coordination du Système des Nations Unies au Niger, Bureau du Coordonnateur Résident. 2015. “Rapport de l’Equipe Pays du Système des Nations Unies au Niger pour le second cycle de l’Examen Périodique Universel (EPU).” June; Government of Niger. 2018. Strategy to Combat Irregular Migration. Niamey. Data card sources: ANLTP/TIM. 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018.” Niamey; Coordination du Système des Nations Unies au Niger, Bureau du Coordonnateur Résident. 2015. “Rapport de l’Equipe Pays duSystème des Nations Unies au Niger pour le second cycle de l’Examen Périodique Universel (EPU).” June.

Trafficking in persons

Women and girls from Niger are at high risk of being trafficked to Nigeria, North Africa, the Middle East and/or Europe for the purposes of sexual exploitation and forced labour. The process of trafficking often begins with false promises of work opportunities abroad, usually made by an acquaintance.

In 2018, 60 victims of trafficking were detected in Niger; women and girls represented the majority of these victims (72 per cent), over half of whom had experienced sexual violence. Just over two thirds received assistance such as legal assistance and support for family reunification by the Nigerien authorities and its partners.

There are various factors that may increase the risk of women and girls to trafficking in persons, including deeply entrenched gender inequalities, poverty, lack of formal qualifications, armed conflicts, limited access to basic services, sexual and gender-based violence and practices such as slavery and servitude. Traffickers prey on these economic and social vulnerabilities, often using deception to lure their victims into forced labour or abduction.

Sources: U.S. Department of State. 2020. Trafficking in Persons Report: 20th Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). 2020. Regional Strategy for Combating Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants 2015–2020. Dakar: Regional Office for West and Central Africa; IOM. 2020. Migration in West and North Africa and across the Mediterranean. Geneva: IOM; National Agency for the Fight against Trafficking in Persons and Smuggling of Migrants (ANLTP/TIM). 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018.” Niamey; Ministère du Plan and Ministère de la Justice. 2016. Enquête sur les Comportements, Attitudes et Pratiques des Populations en Matière de Traite des Personnes au Niger: Rapport d’Analyse. November. Data card sources: ANLTP/TIM. 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018”. Niamey.

Migrant smuggling

Women from Niger and women from other West African countries who migrate through Niger often use smugglers to migrate to North Africa and Europe because of a lack of access to regular migration pathways, limited information on safe migration and lack of legal documentation. 11 In 2018, 66 victims of migrant smuggling heading to Algeria and Libya were detected in Niger. Almost one third of the victims were women and girls from Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria.

Migrant women are at high risk of abuse, including sexual and gender-based violence and abandonment by smugglers, which can have devastating consequences. In October 2013, a group of rescuers found the bodies of 92 migrants—36 per cent of whom were women—abandoned by smugglers near the Algerian border. 13 In June 2016, a similar incident occurred when 34 migrants—26 per cent of whom were women—perished in the Ténéré desert.

Sources: European Commission, DG Migration and Home Affairs. 2015. A Study on Smuggling of Migrants: Characteristics, Responses and Cooperation with Third Countries – Final Report. September; ANLTP/TIM. 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018.” Niamey; Coordination du Système des Nations Unies au Niger, Bureau du Coordonnateur Résident. 2015. “Rapport de l’Equipe Pays du Système des Nations Unies au Niger pour le second cycle de l’Examen Périodique Universel (EPU).” June; Government of Niger. 2018. Strategy to Combat Irregular Migration. Niamey. Data card sources: ANLTP/TIM. 2018. “Rapport de Collecte des Données Administratives, Traite des Personnes et Trafic Illicite de Migrants au Niger: Année 2018.” Niamey; Coordination du Système des Nations Unies au Niger, Bureau du Coordonnateur Résident. 2015. “Rapport de l’Equipe Pays duSystème des Nations Unies au Niger pour le second cycle de l’Examen Périodique Universel (EPU).” June.

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV)

Regretfully, women and girls migrating through Niger continue to be at high risk of SGBV including sexual exploitation and the use of survival sex to gain passage, shelter, sustenance or money for their journeys. There are reports that migrant women have been forced by smugglers into prostitution in brothels in Agadez, in Northern Niger, to make the money they need to continue their journey.

Violence and abuse against migrant women and girls are perpetrated not only by smugglers, traffickers, criminal gangs and fellow migrants but also by law enforcement officials. It has been documented that 61 per cent of incidents of physical abuse reported by migrant women are perpetuated by immigration officials and security forces in Niger.

Almost 40 per cent of migrant women from Niger and other West African countries experience SGBV and abuse during their migration in Niger, Libya and Algeria.

Migrant women and girls from Niger who are subjected to SGBV often do not seek support from authorities for a variety of reasons, including limited knowledge of their rights, lack of evidence, fear of detention and/or deportation, lack of trust in the authorities, perceived stigmatization and being dependent on the person—often an intimate partner.

Sources: IOM. 2017. “IOM Niger: 2016 Migrant Profiling Report”. Geneva: IOM; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). 2018. Alone and Unsafe: Children, Migration and Sexual and Gender-based Violence. Geneva: IFRC; IFRC. 2018. Alone and Unsafe: Children, Migration and Sexual and Gender-based Violence. Geneva: IFRC; UNHCR and Mixed Migration Centre (MMC). 2020. “On this journey, no one cares if you live or die“. Abuse, protection, and justice along routes between East and West Africa and Africa’s Mediterranean coast. July; IOM. 2017. “IOM Niger: 2016 Migrant Profiling Report.” Geneva: IOM; UN Women. 2021. “Rapid Assessment of the Situations of Women Migrating from, into and through Niger.” New York: UN Women. Data card sources: Mixed Migration Centre (MMC). 2020. A Sharper Lens on Vulnerability (West Africa). A statistical analysis of the determinants of vulnerability to protection incidents among refugees and migrants in West Africa. November; IOM. 2017. “IOM Niger: 2016 Migrant Profiling Report.” Geneva: IOM; UNHCR and MMC. 2020. “On this journey, no one cares if you live or die“. Abuse, protection, and justice along routes between East and West Africa and Africa’s Mediterranean coast. July.

Labour rights violations

In 2020, only 21 women migrant workers, mainly from Turkey and France, were granted work authorization by Nigerien authorities. 20 This low number suggests that the vast majority of foreign migrant women work without legal documentation in Niger, exposing them to a high risk of labour rights violations.

In Niger, the majority of migrant women work in the informal economy, as workers in small shops or restaurants, as sex workers in urban areas and as short-term domestic workers. Women migrant domestic workers, particularly those who are undocumented, often experience rights violations such as excessive working hours, lack of rest or annual leave, sexual and gender-based violence, lack of freedom of movement and restricted communication resulting in physical, social and cultural isolation.

Sources: Meeting between UN Women and the National Agency for Employment Promotion on 12 April 2021; International Labour Organization (ILO). 2003. Preventing Discrimination, Exploitation and Abuse of Women Migrant Workers – An Information Guide. Six booklets. Geneva: ILO Data card sources: Meeting between UN Women and the National Agency for Employment Promotion on 12 April 2021; Maiga, D. 2011. “Genre et Migration au Niger.” CARIM-AS 2011/08. Florence: Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

Access to social protection

From January 2017 to April 2021, only 173 migrant workers have been registered with social security coverage in Niger. Access to social protection is dependent on migration status with only migrant women in a regular situation being eligible. Moreover, migrant women are often overrepresented in the informal sector and therefore lack social protection coverage in Niger.

Sources: Meeting between UN Women and the National Social Security Fund on 28 April 2021; UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). 2016. “Committee on the Protection of the Rights of Migrant Workers Considers the Initial Report of Niger”. OHCHR News, 31 August; World Bank. 2019. Review of the Public Expenditures in Social Protection in Niger. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Data card sources: Meeting between UN Women and the National Social Security Fund on 28 April 2021.

Access to information

Migrants in Niger largely rely on information from their personal networks, with friends and family in countries of destination being the main sources of information for migrant women prior to departure. As information obtained from informal sources may not reflect the risks of unsafe and irregular migration, it is critical that women have access to full, accessible and gender-responsive information about the migration process in a language the migrant understands.

Sources: Mixed Migration Centre (MMC). 2019. “MMC West Africa 4Mi Snapshot March 2019“. Data card sources: Mixed Migration Centre (MMC). 2019. “MMC West Africa 4Mi Snapshot March 2019”.

COVID-19

The Nigerien government has adopted a series of COVID-19–related restrictions, such as movement restrictions and quarantine measures, which have made migration more complex and difficult. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly large on migrant women in Niger, who already are some of the most marginalized members of society. A survey carried out by the Mixed Migration Centre found that the loss of income, due to the pandemic, had severe economic and psychological impacts on migrant women, with the impossibility of continuing the journey (33 per cent), increased worry and anxiety (22 per cent) and the impossibility of paying remittances (21 per cent) as the main impacts on their daily life.

Moreover, migrant women were concerned about the lack of access to health services, mainly due to lack of funds (37 per cent), unclear advice regarding testing and treating coronavirus (15 per cent) and fear of being reported to authorities (11 per cent).

Sources: The MMC survey was conducted in Niger between 20 April and 20 June 2020 following an Agreement on the Sharing of 4Mi Data Between The Mixed Migration Centre (MMC) on behalf of the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) And UN Women. Data card sources: MMC survey data set conducted in Niger between 20 April and 20 June 2020; Source: MMC survey data set conducted in Niger between 20 April and 20 June 2020.